Discover our featured or best-selling products

Type: Nespresso® compatible coffee capsules

Dante

Regular price

€3,70

Sale price

€3,70

Regular price

Type: Nespresso® compatible coffee capsules

Box Capsule "Divina"

Regular price

€36,00

Sale price

€36,00

Regular price

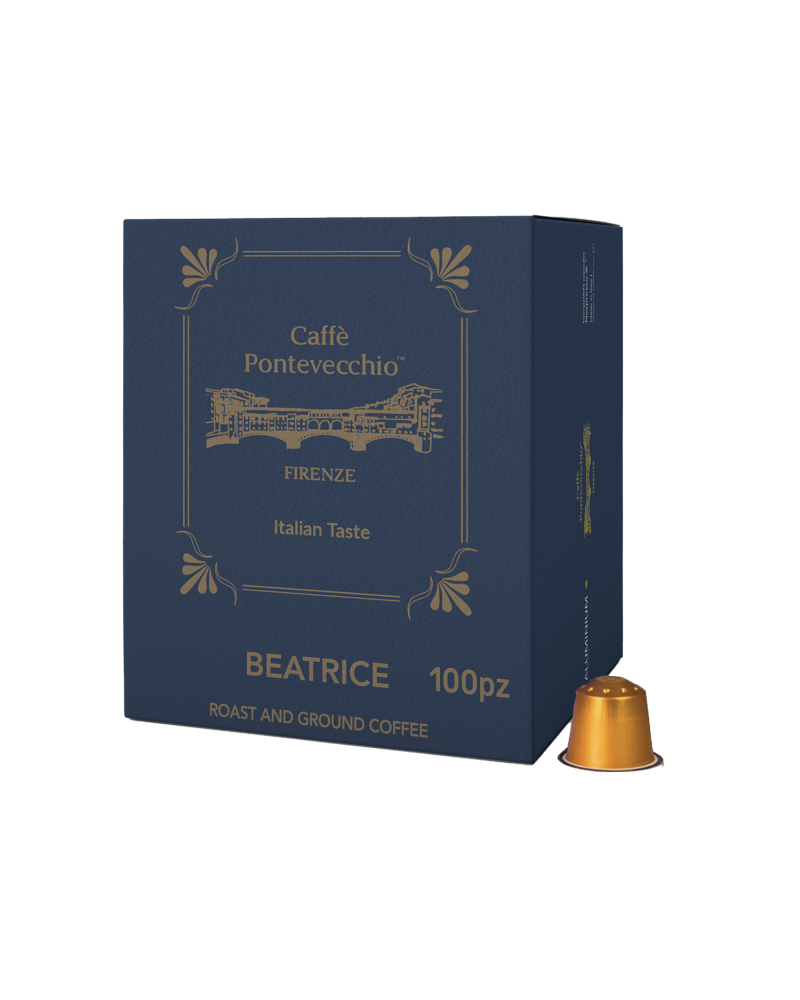

Type: Nespresso® compatible coffee capsules

Box Capsule "Beatrice"

Regular price

€37,00

Sale price

€37,00

Regular price

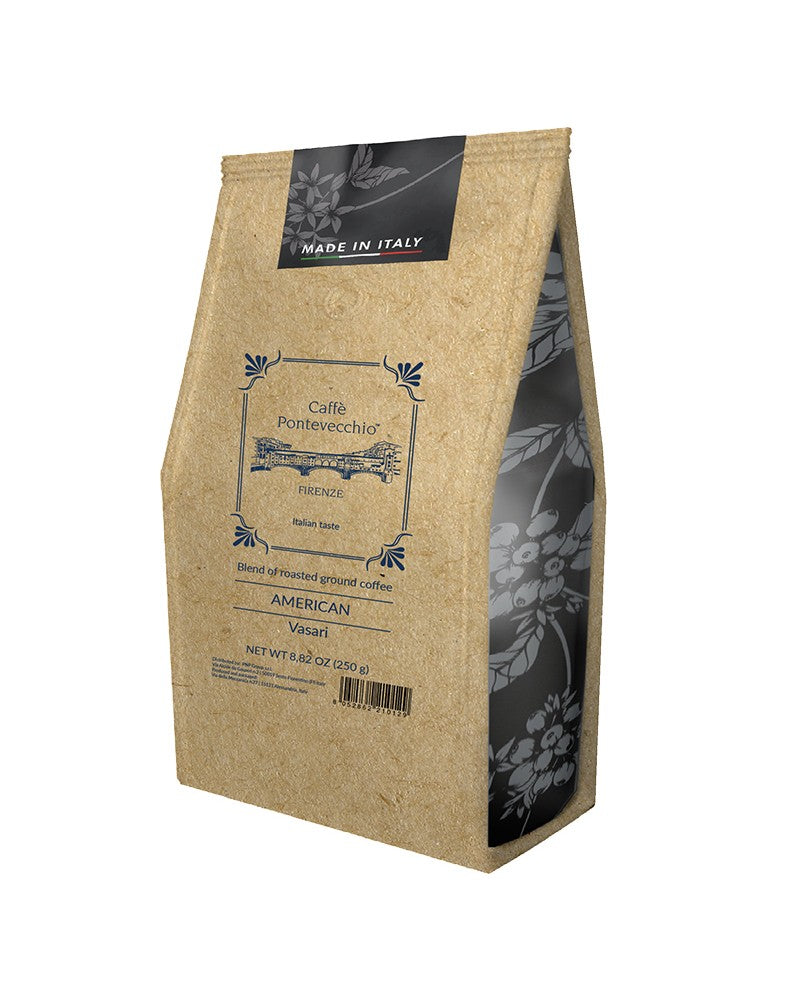

TRADITIONAL COFFEE *

Why our taste becomes unique

- Selection of Raw Coffee

High-quality beans and carefully selected suppliers ensure a coffee that meets high standards of taste and sustainability. - Bean Roasting

Each variety of bean is roasted at specific temperatures and times to enhance the aromas and flavors of its origin. - Coffee Blending

We create exclusive blends by expertly mixing selected varieties to deliver balance and an unmistakable taste. - Coffee Grinding

We carefully grind each blend to achieve the perfect particle size, enhancing every brewing method. - Tasting

Each blend is sampled by our experts to ensure a deep and authentic taste experience.

Fast delivery directly

at your home in 48 hours

Secure payments

Our customer support team is

always available to help you

Exclusive blends

for true connoisseurs